Tonglei Li, Ph.D.

Tonglei Li, Ph.D.

Editor-in-Chief, Pharmaceutical Research

Over the last several years, AI and ML have taken the world by storm. These abbreviations have become words of their own, much like ChatGPT and LLM, radiating a futuristic coolness. While attending recent drug development conferences, I was often inundated with various talks that had AI or ML in their titles. As an editor, I have also observed a steady increase in the number of manuscripts that attempt ML in their studies or review technical concepts and their applications in drug research. It seems to be on everyone's mind that AI/ML will transform drug discovery and development, just as LLMs are reshaping how we communicate. The sentiment creates both excitement and anxiety. For researchers trained in pharmaceutics to adopt AI/ML in their work, where should one begin?

As a computational chemist, I started applying ML to study molecular interactions a few years ago. I was reluctant at the beginning, brushing off ML as just regression. As you may see below, I was not entirely wrong. But after developing several ML concepts and methods for molecular representation and property prediction, I am fully convinced of ML's prowess thanks to its statistical principles. In this brief perspective, I want to share some key lessons I have learned.

First of all, ML is nothing new, and each of us has practiced some forms of ML regularly in our research. The simplest model may be linear regression, which already includes the core ingredients found across ML approaches, that is, input feature(s), x, output label or target property, y, model architecture, y = ax + b, and loss function (e.g., mean squared error, or MSE). Above all, we utilize a set of existing data points and optimize the loss function to identify proper values of a and b. In more advanced ML approaches, the model architecture can be nonlinear (as in support vector machine, or SVM) or even nonparametric (as in Gaussian Process, or GP); it may use matrix algebra (as in artificial neural network, or ANN) or binary recursive partitioning (as in decision tree).

The nature of ML is to seek correlations between inputs, x, and outputs, y, to make predictions for new inputs or unseen data eventually. As the devil is always in the details, complexities arise when approximating such relationships. One conundrum arises between the need to fully describe the input, often with a high-dimensional representation, and the limited availability of training data. For example, dozens or even hundreds of descriptors are regularly utilized to describe a molecule when predicting its physicochemical properties. As the feature space grows exponentially when increasing feature dimensions, the amount of training data becomes dwarfed by the feature space of input x. The mismatch leads to the so-called Curse of Dimensionality, making it extremely difficult to derive a meaningful relationship between the input and output variables. Dimensionality reduction of the input features, for example via PCA (principal component analysis), is necessitated to effectively learn from the data and mitigate potential data overfitting. Nonetheless, dimensionality reduction can lead to information loss and feature granulation, thereby deteriorating model predictivity.

In addition to molecular descriptors, a molecule may be represented by SMILES, fingerprint, or graph for ML applications. Many molecular encodings are high-dimensional. For instance, Morgan Fingerprint utilizes 1024 bits (or even 2024 bits) hashed out of molecular structural attributes. It is equivalent to 10^308, considerably exceeding the commonly estimated chemical space of 10^60. Moreover, high-dimensional molecular descriptions often lead to chemical sparsity, meaning that the majority of the feature space does not represent valid molecules but rather mathematically sound constructs. An analogy I often used to illustrate this point is 4-letter English word. There are about half a million combinations of 26 letters, but there are only about five thousand actual English 4-letter words. In this case, 99% of the space is filled with English-like mumbo jumbo that lacks real meaning! It is unlikely to make a meaningful prediction but hallucinate in this space.

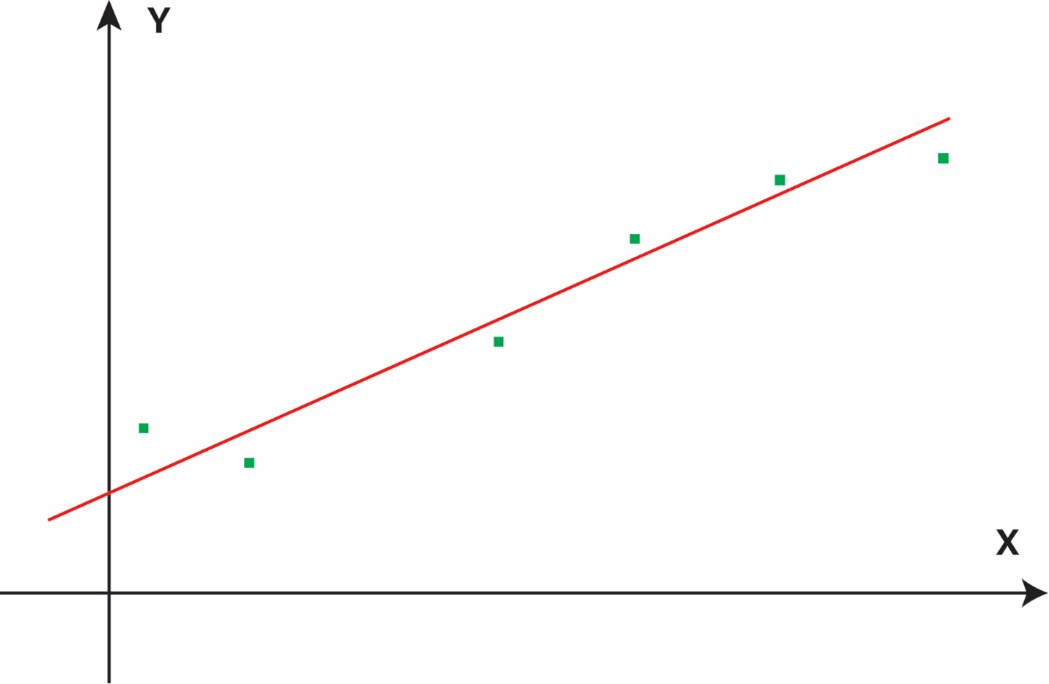

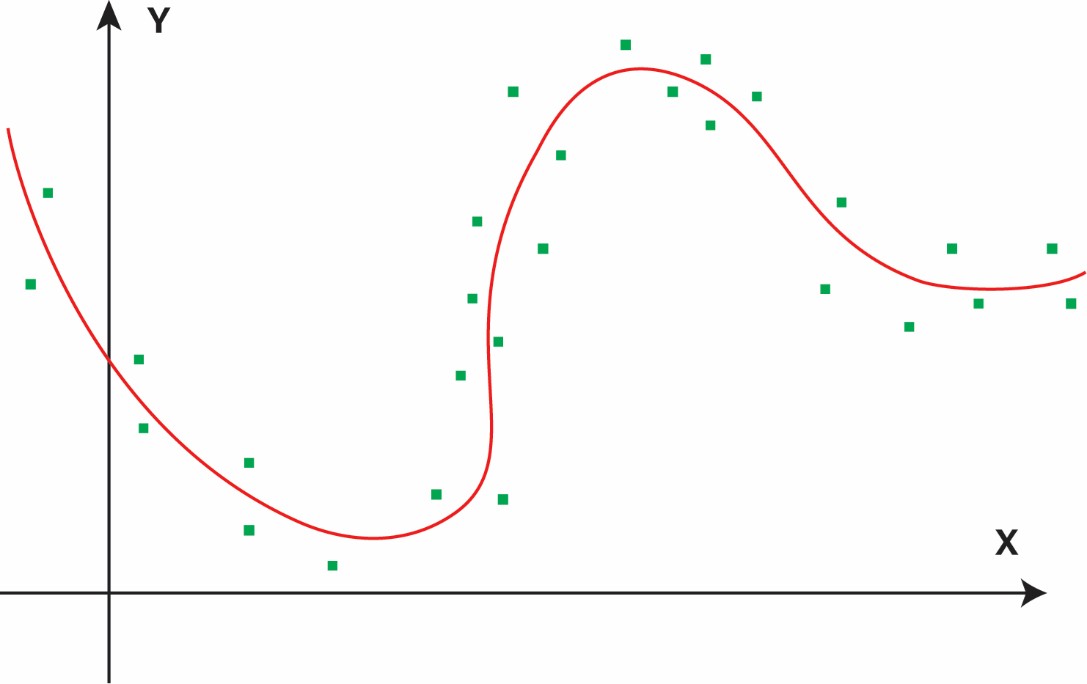

As such, an ideal molecular representation should be low-dimensional, chemically dense, and directly associated with the property of interest. These attributes will ease the training of an ML model and enable it to learn the underlying correlation from a limited amount of noisy experimental data due to measurement uncertainties. To illustrate these points, I created several simplified figures. Obviously, a linear relationship between x and y is easiest to learn, requiring few data points (Figure 1a). In this case, some prior knowledge of the x-y relationship may already be encoded in the feature representation. When the underlying correlation becomes more complex or nonlinear (Figure 1b), a lot more data points are needed. The need for more data points becomes exponentially necessary when x is high-dimensional due to the Curse of Dimensionality. When the input is sparse (Figure 1c), there is no chemical data in the chemically invalid, yet mathematically feasible, regions. Sparsity will make learning difficult and prediction hallucinatory, as the correlation function becomes discontinuous.

Figure 1a: Linear relationship—few data points suffice when representation aligns well with the property

Figure 1b: Nonlinear relationship—more data or stronger priors/representations are needed

Figure 1c: Sparse input space—regions lack chemically valid data; extrapolation becomes risky without constraints.

Machine learning is not a magic wand. It is deeply rooted in statistical principles. For drug research, how we present a molecule is essential. If its description is high-dimensional, its dimensionality must be reduced to cope with limited training data. Even after dimensionality reduction, ideally, the input features should retain the most chemical information and have direct, linear relationships with the output property. ML cannot replace chemical insight; it should amplify it with strong representation and rigorous architecture.

About the author

Dr. Tonglei Li is a professor in the Department of Industrial and Molecular Pharmaceutics at Purdue University. He was trained in chemistry, computation, and pharmaceutics. Dr. Li has recently developed several molecular representations for machine learning based on molecular quantum information (PMID: 38862828, 41108227). He and his group have utilized and expanded these concepts for predictive and generative AI/ML applications in drug research. Dr. Li is currently the Editor-in-Chief of Pharmaceutical Research, an AAPS-affiliated journal.