Economist Offers New Approach

By Rebecca Stauffer

By Rebecca Stauffer

Each year biotech companies’ funding challenges exponentially grow. Investors are wary of funding research that fails to produce a therapeutic candidate or results in a product that can’t win approval. Meanwhile, expenses continue to multiply.

Andrew W. Lo, Ph.D., Charles E. and Susan T. Harris Professor and Director of the Laboratory for Financial Engineering at the MIT Sloan School of Management, has spent years studying the biotechnology sector—or the biomedical ecosystem, as he calls it. He believes that bridging the gap between the science and business of drug development with new business models and financing structures that better align the interests of all stakeholders could upend what has traditionally been a volatile industry, and he has spent the last 10+ years developing and testing his ideas.

He showcased some of the models he and his colleagues have developed at the AAPS National Biotechnology Conference in May.

A financial economist, Lo’s research into the economics of biotech began during a six-year period in which he watched friends and family develop various cancers, including his mother who died of lung cancer in 2011.

“I discovered pretty quickly that a cancer patient needs a financial economist about as much as a fish needs a 401(k) plan,” he said. “But the more I learned about cancer drug development, the more convinced I became that finance plays a pretty big role drug development. I began to spend more of my time thinking about how I could apply what I knew—financial engineering—to see whether or not there is a way to bring more resources to drug developers.”

Lo’s thinking may be especially important now, as the biotech market continues to battle a financial slump and the promise of gene therapies are questioned.

“We are living through a very unusual period in biomedicine—an inflection point,” Lo said.

Treatments for Canavan disease represent this inflection point. This rare inherited disorder of the nervous system is most common in infants who begin to lose gross motor skills between three and nine months. Symptoms progressively worsen, and most pediatric patients do not live past the age of 10. A single gene mutation prevents repair of the myelin sheath layer around neurons.

At this time, potential gene therapies may offer a treatment for the disorder—and possibly a cure. Lo presented a video of a toddler receiving a single dose of an experimental treatment. Within seven months of receiving it, she was walking with a walker—something historically not possible for a patient with her stage of Canavan disease. Nine months after the gene therapy, she was walking on her own.

Science is Changing – But Its Funding Strategy is Not

A 2016 MIT report refers to the “convergence of the life sciences, physical sciences, and engineering,” as a new paradigm that also includes the “omics revolution.”

But according to Lo, one “omics” in particular has been a bottleneck—“economics.”

“The business models we’re using are still the same old models we’ve used for half a century, and they’re not ideally suited for funding biomedical R&D,” he said.

Lo entered the funding discussion as an outsider and found himself quickly directed by industry to the “the Valley of Death” as their main funding woe.

“Initially, I wondered what southern California had to do with biomedical innovation, and then someone told me, ‘It’s not a place, it is a metaphysical challenge between basic scientific research and clinical studies,’ where it’s particularly challenging to raise funds.’”

After studying the biomedical market for a few years, however, Lo came to a different conclusion.

“The reason we have a Valley of Death is because of increasing risk and uncertainty. Risk is the kind of randomness you can parameterize using normal distributions, probabilities of success, and so on,” he said. “Uncertainty is the unknown unknowns that you can’t parameterize.”

Both risk and uncertainty have been increasing in biomedicine even as pioneering treatments are studied. In his area of expertise, investors reduce risks by building knowledge, such as studying the balance sheets of a company to determine financial health.

This is not the case for biotherapeutics research.

“When you make a discovery and develop a new drug, that’s fantastic for patients,” Lo said, “But that’s not so great for the investors who put money in the existing drug you just put out of business with your breakthrough.” He used the example of Spinraza. Three years after it received FDA approval, Zolgensma was approved, making the former obsolete.

“The smarter you get, the riskier it gets for us investors.”

What Do Investors Look for in a Company?

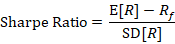

Investors generally rely on a calculation called the Sharpe ratio to determine risk-adjusted return.

This ratio compares the expected return of an investment above the risk-free return to the risk of that investment, as measured by its return standard deviation. The higher the Sharpe ratio, the better the average return relative to its risk.

“Biomedicine has had a Sharpe ratio that’s been declining over the last several decades,” Lo said. “Not because the numerator isn’t attractive. There are plenty of biotech companies that make lots of money for their investors. The problem is that the denominator has been growing even faster. Not despite, but because of, all of the breakthroughs you all are pioneering…that really is the challenge of drug development.”

He then listed seven challenges he sees in drug development.

1. Complex value propositions (science/engineering)

2. Large upfront capital needs

3. Long gestation lags

4. Little or no intermediate cash flows

5. Low/unknown probability of success

6. Binary outcome (“You either make money with an approval or lose everything if it doesn’t get approved.”)

7. Huge payoff if successful

“In finance we have a very special term I coined for such an investment. I call it a ‘long shot.’”

Long shots, he emphasized, cannot be financed like other investments.

If a commercial developer runs out of funding, a half-completed building project can be sold and completed by another developer. Not so with a half-completed drug trial.

“Not only is it worthless because you don’t have an approval, but it’s worthless for a much more important reason,” Lo said. “If a drug program runs out of money, the scientists and clinicians that are developing the drug stop getting paid, and when they stop getting paid, they’ll leave and go to other jobs.

“How much is your drug worth without the people who created that drug? Generally, unless you’re close to an approval, not a whole lot. Unlike many other industries, people are the life blood of a biotech company.”

New Equation for Improving Investment Likelihood

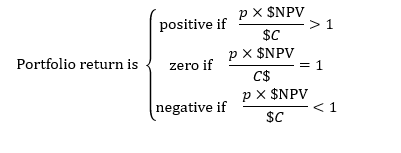

To address the chronic underfunding of promising but risky therapies, Lo developed what he calls the “Fundamental Law of Healthcare Finance”—a simple yet powerful framework that captures the core financial trade-offs in therapeutic development, inspired by the same risk–return logic that underpins the Sharpe ratio.

Lo began describing this framework with the following thought experiment. Imagine a portfolio of n drug development programs where: each one cost $C from preclinical beginnings all the way to FDA approval; took m years to complete; had a probability of approval of p: and if approved, would generate cumulative earnings over its entire life equivalent to a single payment of $NPV on the date of approval. This set-up leads to a very simple expression that determines whether the portfolio will generate a positive, zero, or negative rate of return for its investors:

“The reason I call this the ‘Fundamental Law of Healthcare Finance’ is this one simple little equation contains the entire process of developing a drug candidate from beginning to end,” Lo said. “It contains the science (the probability of approval, p) the medicine (the cost of running the trial, $C), and the pricing and reimbursement policies, peak sales estimates, impact of competitors, etc. once the drug is approved ($NPV).

“Now you know how what you do affects the bottom line. Better science means higher p; better clinical trial design means lower $C ; and better sales practices means higher $NPV, all of which lead to more attractive returns for investors and, consequently, more funding for drug development.”

Understanding the economics of financing in this way could allow biotech firms—and pharmaceutical scientists—to get more funding for bringing innovative therapies to market. The key is for research teams to use better science and reduce risk more proactively, including the use of financial engineering to manage risk.

“Investors are willing to take risk, but they want to know that the risk they signed up for is what they’re actually getting,” Lo said. Over the past several years, he has engaged with biotech leaders on these models and their applications. He has also co-written a textbook on biomedical innovation financing to help stakeholders better assess risk and reward in drug development.

“The bottom line is that biomedical and financial experts need to collaborate, and although the culture of those two fields are very different, there is a huge amount of value in bridging that gap,” he concluded.

SAVE THE DATE

On Sunday, November 9 at the 2025 PharmSci 360, Richard T. Thakor, Ph.D., Associate Professor of Finance at University of Minnesota, Carlson School of Management, and a Research Affiliate at the MIT Laboratory for Financial Engineering, will deliver the opening plenary. His research focuses on empirical and theoretical corporate finance in the areas of R&D and innovation, healthcare finance, financial institutions, and the effects of financial frictions on firm investments.